Pelkie: A Century of Finnishness in the American North Woods.

Pelkie faces, stories and family photos will make the film. Especially Stories. Although almost completely broken from its Finnish past, a few Pelks will tell stories about lifeways: Spring floods, skating parties, river swimming, great teachers, hockey teams, Co-op Store, speaking and hearing the Finnish language, Cheese Factory, skiing Limestone Mountain, making hay, picking cabbage, colorful characters, spraying DDT and on Saturday evenings, watching the smoke wafting lazily upward from saunas throughout the countryside.

(More options to donate at the bottom of the page.)

Pelkie Trailer

Finnish Folk Art Sample

For the Scandinavian-American Foundation Proposal

A Brief Historical Sketch of Pelkie

During the 1860s and 1870s, while the trend in America was to migrate from country to city, Finnish immigrants began settling the remote sections of land still open to homesteading in the northern parts of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and the Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The lure of free land was so irresistible to impoverished and landless Finnish laborers, that groups pooled their scarce resources to send someone ahead to America to assess homesteading possibilities. These “land scouts” reported back on how and where to apply for homesteads. Following this pattern, in the middle 1860s, early Finnish immigrants proceeded directly into the wilderness settlements of Franklin and Cokato. In 1870 they moved into Holmes City MN, in 1874 into New York Mills, MN and in 1890 into Pelkie, MI. Throughout the 1880s the back-to-the-land “secondary” migration continued.

In the 1870s, migration from Calumet to rural areas began. Land-hungry immigrants moved to remote hamlets in Minnesota and South Dakota. Between 1890 and 1930, most of the arriving Finnish immigrants settled in Michigan’s Copper Country to work in mines. Known to them as Pessapaikka (nesting place), Calumet became the hub of the Finnish American community

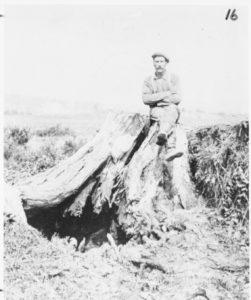

Secondary migration from the mines to pine stump-filled subsistence farms soared from 1900 to 1920. It was fueled by the turmoil of the 1906-1907 great mining strikes on the Minnesota Iron Range, and in 1913 by Michigan’s Copper Country. Thousands of disenchanted miners, many of them blacklisted for supporting the Western Federation of Miners, settled into the cutover, once-forested lands, surrounding the mining towns. This began the social movement wave of Finnish immigrants moving into an area first called King’s Landing, then KyrÖ and it eventually became known as Pelkie.

New farmers cleared gigantic white pine stumps from their cut over homesteads. They built saunas, barns and log homes. During the winter months farmers worked as lumberjacks and their wives and children tended the farm and cattle. April’s melting snows saw men returning to their family farms to raise crops and milk cows. Sometimes lumberjacks would help the farmers in return for food and lodging.

Farmers pooled their funds together to buy bulk quantities of grain and essential farming supplies. In 1918, mutual consumption practice evolved into the Farmers Co-op Trading Company, with 109 members, doing a yearly business of $37,800. A decade later, sales had doubled. The Co-op was eventually renamed the Pelkie Co-operative Store. It added a creamery and cheese factory and joined the Central Co-operative Wholesale Association. Until it closed in 1995, the Co-op provided a wide range of goods, equipment repair services, and employment for residents.

To transport copper ore from Mass City to a stamping plant in Keweenaw Bay, 27 miles away, the Mineral Range Railroad ran a line through Pelkie in 1900. By 1916 the stamp plant closed, so trains transported milk, cabbage, and hardwood logs from Pelkie to the mining towns.

Finnish American immigrants had an average of 6.5 children. Their second generation dramatically expanded the local population. In 1932, Pelkie’s eight one-room neighborhood schools closed and the Pelkie Agricultural School opened. The huge cohort of 2nd generation offspring filled its seats. Three Lutheran churches, a private store, Co-op, post office, blacksmith shop, gas station and a socialist dance hall served the growing community.

Based on a sample of 359 2nd generation Finnish Americans from Pelkie, 73 per cent married Finnish Americans and had an average of 2.5 children. Three out of four migrated toward urban employment, primarily to Detroit. Of those who left, within ten years, 42% returned (Loukinen 1982). They had a remarkably deep attachment to their home community. Their high in-group marriage patterns sustained Finnish culture in Pelkie throughout their lives.

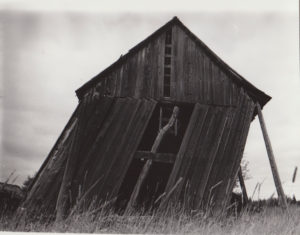

Farm kids in 1936 saw their railroad tracks disappear and by the late 1950s, dairy farming started its long decline. Milking cows presented a bleak choice to the 3rd generation immigrants’ grandchildren. This generation was well educated but almost everyone lost their Finnish language. Seventy percent left Pelkie chasing careers. Only 7% returned. Whereas, of their parents, 73 per cent married Finnish-Americans and their grandparents married close to 90 per cent. In-group marriage rate for the third generation was only 40 per cent (Loukinen, 1997). A few of the 2nd but primarily this 3rd generation will tell the Pelkie story.

Today Pelkie is an ethnically and occupationally mixed community. In the 1970s a few counter-culture families moved in to be close to the land. A few 3rd generation Finnish American remnants were lucky enough to find a way to earn a living without moving: two raise beef cattle, one raises hogs and one dairy farmer remains. No cabbage farmers are left. Mennonite families moved in one after the other and they purchased the historic Kyro Evangelical Lutheran Church. They produce eggs, jams, jellies and beef cattle. Casino and state prison employees also bought homes but they are isolated from the larger community. Pelkie has five churches and no store, a post office with very limited hours and an auto repair shop. Junk litters some small homes on the main road. A 96 year-old, long time teacher at the Pelkie School, now in a nursing home, refuses to return because the main street area looks so junky and dilapidated that it depresses her.

How will we do it?

Over four decades I have built a personal network of Finnish American history and cultural experts. Many of whom will contribute for the intrinsic value of the film, and because they are friends. Some need to be paid. Talented Finnish American cultural experts, photographers, videographers and digital artists will do much of the legwork. This is far less than the prevailing rate.

In my recent PBS documentary, Winona: A Copper Country Ghost Town (2016), I framed the narrative to provide a general historical view of the Copper Country. I will frame a Pelkie film to provide the background of Finnish immigration to America and the settling of the very many Finnish American farming communities in our Western Lake Superior Region, communities like Pelkie. To the extent that I develop a larger international and regional frame, it will require additional travel and the paid services of others, hence a greater cost for a longer film.

Am I too late? Yes, of course. Everyone has said this for 35 years of my filmmaking. One is ALWAYS late. Important elders had died before I started every cultural documentary project. Nevertheless, I have made 13 documentaries that have won national and international awards when submitted to such anonymous, juried competition. This can be a very good one. This would be a wonderful way for our Upper Peninsula to celebrate the centenary of Finland’s Independence (1917) by highlighting the many communities settled by Finnish immigrants and tracing their origins back to Finland.

Work done. I have completed an unusually large body of preliminary research between 1972 and 2017: hundreds of pages of transcriptions and black and white still photos from interviews with many 2nd and some 3rd generation (children and grandchildren of immigrants) Pelkie residents.

We have already recorded video interviews with Hildur Larson (1901-1992), Donald Lehto (1913-2012), Leonard Pelto (1920-2017), Mildred Tepsa (96 years), Rudy Tahtinen (88 years) and Ruben Turunen (88 years). We have also video-recorded funeral celebrations of life for Donald Lehto and Reuben Niemisto. This preliminary work has reduced the research cost of the project.

Michael Loukinen

Director